|

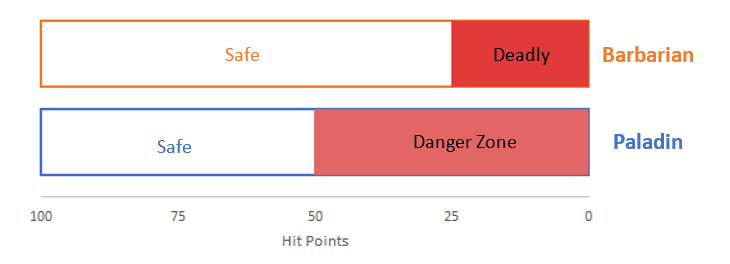

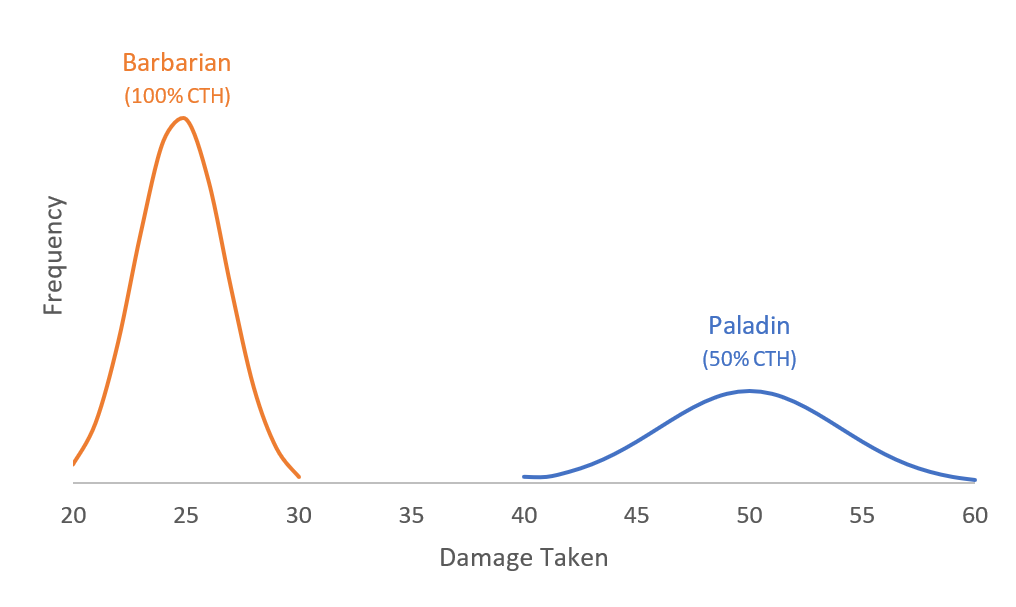

Tank: a character whose primary role is to absorb damage as a means of protecting allies 5e classes can tank damage in a few different ways. Paladins and Fighters can be ‘AC tanks’, who reduce incoming damage by being difficult to hit and having solid saving throws. Rogues and Monks, while they don’t usually serve as a blocker to protect allies, avoid damage through ‘dodge tanking’ – using abilities such as Uncanny Dodge, Evasion, and Deflect Missiles to nullify or reduce damage when hit. Moon Druids can be ‘sponge tanks,’ using their Wild Shape as a disposable HP pool to soak up huge amounts of damage. Barbarians are also ‘sponge tanks’ of a form, using damage resistance to halve incoming damage and simply, well, ‘tanking it’ with their massive HP pool. A cynic might say that if these methods were perfectly balanced, it really doesn’t matter which method you use – all will work out equally well in the long run – and the difference is more for the sake of appearance than anything else. Naturally, my strawman cynic is wrong, and for a number of reasons, but the one I’m looking at today is the impact of variance on planning. Let’s consider a Paladin and a Barbarian, in a heavily abstracted scenario. A monster hits for 50 damage. The Paladin has a 50% chance to avoid being hit, while the Barbarian will definitely get hit but only takes 50% of the damage. Both start with the same HP. Who dies first? At first glance, this might seem to be a draw. Both have the same expected (average) damage—25—so over an infinite number of attacks, we’d expect them to lose HP at the same rate. As they do not have infinite HP, however, the threshold becomes quite important. If they have 40 HP, the Paladin could die in one hit, while the Barbarian will not. If they have 20, the Barbarian is faced with certain death, while the Paladin might get lucky. Maybe this doesn’t appear that useful. If you’re really low, you want to be the Paladin; if you’re doing ok maybe you’d prefer to be the Barbarian – so what? Given you can’t just switch classes on the fly is it really true to say that one is better off in general? Yes. Yes it is. Imagine they have exactly 100 HP. Neither is at immediate risk of death, and on average we’d expect both to die on turn 4. How should each approach the encounter? For the Paladin, that’s a complex question. If they’re unlucky, they could die in two hits. They know they’re safe until they take damage the first time, but at that point all bets are off. Can the Paladin defeat their opponent quickly, or are they willing to gamble with their life? For the Barbarian, planning is much easier. They will die on the fourth turn. Can they defeat their opponent before then? If so, the combat is safe. If not, they should flee. In actual games, we have to account for variance from the damage dice as well. The monster could roll higher or lower than expected. Here, too, a Barbarian’s damage resistance reduces the variance: by halving the incoming damage, the difference between minimum and maximum damage rolls is less for the Barbarian than other classes. Less variance again means a better ability to predict outcomes, and more options in combat. The fundamental difference between these two modes of tanking is in outcome variance, and that affects their ability to plan an encounter and take calculated risks. With less uncertainty to account for, a Barbarian is better able to plan their actions in combat, and can expect a greater degree of success.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed