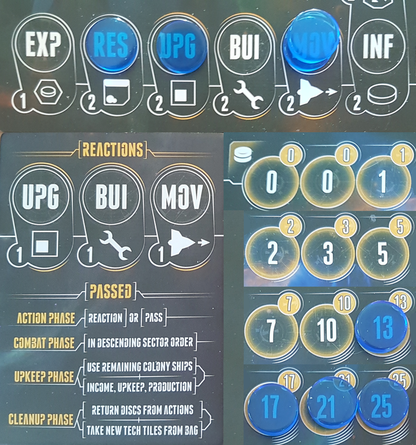

Well, it's been a couple of months since I wrote an analysis post, which makes it high time for another one! And, though the last post I made was also about Eclipse (2nd Edition), I'll be damned if it isn't the best-designed board game I've played in a long time, so here we go again! Last time, I wrote about how game designer Touko Tahkokallio reduced the combat disincentives that often plague similar games. This time, I want to take a look at something else he handled superbly well in Eclipse: passing. Eclipse, like most board games, is sequential and turn-based. One player takes their turn, then the next, and so on around the table. Each turn taken carries an increasing upkeep cost; a player may instead pass. Once all players have passed, the round ends: combats are resolved, income, upkeep and resource production are calculated, and new technologies become available before the next round begins and play resumes. This is all standard fare so far, and games that follow this pattern typically treat passing as a simple, functional mechanic: once they've taken as many turns as they want to or can afford, the player declares that they pass, and sits out the remainder of the round until all other players have done the same. This certainly isn't bad per se, and there's a lot to be said for not overcomplicating things unnecessarily, but I'm a huge fan of the systems Mr. Tahkokallio has put in place to turn passing into a complex and interesting decision, as important in a player's strategy as any other aspect of their game. In Eclipse, passing doesn't bar you from the rest of the round, but neither is it simply a 'no action this turn' option – any further turns taken before the end of the round carry heavy penalties. After passing, a player is restricted on future turns to 'reactions', a severely-limited version of the 'actions' taken normally. As a reaction, the player can only upgrade, build, or move (losing the options to research tech, explore new sectors, or move influence discs), and their upgrade/build/move is less efficient – a player might be able to move two or three ships with a normal action, but as a reaction is restricted to just one. Even worse, these reactions still increase the player's upkeep cost by the full amount, just like any other turn. In a long enough round, a player who played action - action - pass - reaction - pass - pass - reaction would be paying four turns worth of upkeep. Why, then, would a player pass before being certain they'd done everything they wanted to? Well, normally, you wouldn't. There is, however, a good reason they might pass earlier than is necessary, and one very big reason they might delay passing as long as possible. We'll start with the first one: why pass before you have to? The answer: first-to-pass bonuses. The first player to pass gains several advantages. First, you immediately receive a small monetary bonus, which could afford you a reaction if you're broke, or (much more efficiently), an extra action in the next round. Second, whoever passes first gets to start the next round, which comes with first pick of any new technologies, and places that player perfectly to eventually be the first to pass in that round as well, reaping these benefits all over again. Of course, you may have spotted already that if you pass first multiple rounds in a row, you've given up much of the benefit of the cash bonus – taking several extra turns down the line is less efficient in terms of upkeep, and a turn taken now gives immediate benefits. On the other hand, an extra turn in the current round will likely hand the first-to-pass bonuses to someone else. Perhaps you could pass early to deny others the bonus, then use the cash to cover the inefficiency of taking two reaction turns to do something that could otherwise be done in one... but even then there are no guarantees the round will last two more turns before everyone has passed. Of course, if you were to play a couple of extra turns this round after others have passed, you'll have less to do next round and will be more easily able to grab the first-to-pass bonus then... you can see how passing strategy becomes important! As for the reason you might delay passing as long as possible, even with the ever-mounting turn costs – the best time to invade a player is right after they pass. As reactions are only half- or one-third as efficient as actions, you'll be moving twice as many ships as they can scramble in defence, or upgrading your ship designs to exploit their vulnerabilities twice as fast as they can counter-upgrade in response. Of course, this is if you can afford to take all these actions in the first place... perhaps it was worth passing first several times to build up that cash reserve after all? In most other games, passing mechanics are functional, but unnoteworthy. As with so many elements of Eclipse, designer Touko Tahkokallio has gone the extra mile and turned it into an important, interactive, and rewarding aspect of the game. Absolutely phenomenal design.  I’ve just picked up a new boardgame: Eclipse (2nd Edition). As well as being fantastically fun to play, it’s also supremely well-designed. One element in particular is how Eclipse addresses some common 4X problems around instigating combat: attacker’s guilt and a higher combat risk for attackers. Particularly in boardgames, where players are sitting face-to-face, many players are uncomfortable with unprovoked aggression, even when the game requires it. Even a successful attack, if unprovoked, can leave the player feeling bad for victimising someone who did nothing to deserve it. This is natural, it is human, and, for designers, trying to avoid this problem can be frustrating. The root of the problem, I think, is the losses of the ‘victim’ relative to uninvolved parties. We don’t see the same reactions to profiteering, for example, where one player exploits the position of another to gain money/points/whatever without that player losing anything in the process. We also don’t see the same reactions in two-player games: the game unavoidably pits the two players against each other, so there is no victimisation. I believe that the problem arises specifically from the fact that the victim was targeted over other players, and has lost something. A related problem is the attacker’s risk: what if they attack and lose? Attacking usually costs something: in Eclipse, it costs turns, which translate to both time and money, and it risks ships, which have value. If the attacker then loses the battle, they’ve lost time, money, and ships, all to hand an opponent a bunch of points. This represents a far greater loss than the defender risks, and so disincentivises players from attacking unless they can muster overwhelming force. It is the uninvolved third parties who often get the best outcome. They risk nothing, lose nothing, come out objectively better than the battle’s loser, and may be in a good position to threaten the winner of the battle, who may have gained points or territory, but likely suffered some material losses. It may be better to sit back and wait for others to attack, than to go on the offensive yourself. These factors all discourage players from attacking, which can result in wargames involving rather less direct conflict than one might expect from the name. So, how did Touko Tahkokallio, Eclipse’s designer, solve these problems? Several factors combine to reduce the losses suffered by an unsuccessful defending player:

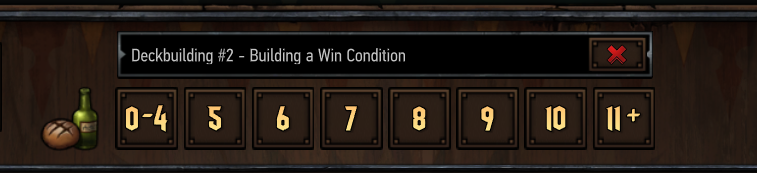

Fantastic design, and only a small part of what contributes to the game’s enjoyment! Last time, we talked about the three fundamental features of a deck. Today, we’re looking at the first of those – your win condition. This is the deck’s game plan; the main strategy you will use to win, and though they can come in many forms, most are centred around a particular mechanic. They’re also a good place to start – when I build a new deck, the first thing I do is pick the mechanic that will be my win condition. Then, I look for cards to support that win condition by pursuing a series of questions:

Let’s have a look at how this works in practice: I’ll build a deck from scratch, starting today with the win condition. Step One: Find an Interesting Mechanic First, we need to pick a win condition. This really is as simple as it sounds. Almost anything can make a win condition, so my advice is this: just pick a mechanic that is somehow related to points—any mechanic you like—and try to build a deck around it. Here’s where I started with this deck: I found an interesting mechanic. Greater Brothers can gain armour by spending coins or damaging itself. Iris: Shade strips all the armour off something and boosts herself by the armour removed. So, here’s the plan: we stack a whole bunch of armour on Greater Brothers, then use Iris: Shade to convert it to points. Step Two: Identify Exploitable Features This is where the questions come in. How can I exploit the features of these cards? How does this mechanic work?

What features of this mechanic are exploitable?

What tools do I need to exploit these features?

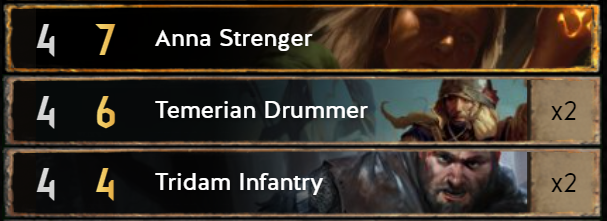

Step Three: Find Cards for Your ‘Shortlist’ How can I get these tools? At this stage we don’t care about deck size or provision budget—that will come later. For now, we’re just making a list of useful cards. If it seems useful to our win condition, it goes in the deck. Let’s take a look at the options. Tools: More Armour on Greater Brothers, Efficiently A quick search for ‘armor’ returns 18 results among Syndicate and Neutral cards. Excluding cards which are already in the deck (Greater Brothers and Iris: Shade), cards used to remove armour, and a couple that only appeared because their name contains the word, we’re left with six cards that can give armour to Greater Brothers:

All of these go in the deck (for now, at least – remember, we’re just gathering a shortlist). We’re on the lookout for other cards that work nicely with armour synergies as well. Looking through the results for ‘armor’ and ‘barricade,’ I find a few:

Tools: More Points on Greater Brothers, Efficiently I search for ‘boost’ and look through the results. Most of the cards shown boost themselves, but a few could be efficient ways to boost Greater Brothers:

Boosting isn’t the only way to put points on a unit, however. Greater Brothers can damage itself with Insanity, so the ‘heal’ and ‘reset’ keywords may be useful as well.

Step Four: Assess Limitations Remember earlier, when we noted that stacking points on Greater Brothers keeps them safe from tall removal, but only if we have last play? Every win condition has weaknesses, limitations that we need to plan for and work around. By this point, we’ve assembled a preliminary shortlist of cards that seem useful to our win condition. This should be enough to give us an idea of how the win condition will work, and let us identify some problems. Problem One: This win condition is single-use. We only have one copy of Greater Brothers, and one copy of Iris: Shade, which means we need some other way to get through the other rounds. Problem Two: The Greater Brothers combo is poorly suited for Round One. Because all of our points are stored as armour, we have very few points actually on the board during the round. If we used the combo in Round One, our opponent could pass whenever they wished, and we’d still have to take another turn to play Iris: Shade and convert all that armour into points. Problem Three, we’ve actually noted already: After converting the armour into points, we have one massively tall unit that’s horrifically vulnerable to tall removal and resets. If we don’t have last play, we’ll lose a lot of matches like this. So, our combo needs to be played in the final round, and we want last play. That means we need either another strategy to reliably win Round One, or a way to gain card advantage. We have a few options: 1. Put in another package that can reliably win Round One Pros:

2. Use armour-synergy cards like Dire Mutated Hound and Living Armor in Round One Pros:

Pros:

In situations like this, if I’m not sure which option is best, I’ll often create incomplete decks for each of the options I like, then compare to see which I like more. In this case, I actually put together a number of decks using different Round One packages. For this article, however, we’ll go with something between options one and two. Our Round One strategy will remain built around armour synergy with Dire Mutated Hound and/or Living Armour, but we may include some expensive non-armour powerplays as well.  Step Five: Refine Your Core Package We have a collection of cards that might be useful, and a good idea of our win condition’s strengths and limitations. Now it’s time to refine that shortlist into a strong core package. There's a few easy inclusions:

...and a few easy exclusions:

The rest of it is a bit trickier. Try not to agonise over these decisions too much when building your own decks – it's easy enough to remove a card or add one back in later.

I'm adding in a new card as well – Necromancy. Our Wagenburgs will be in high demand in all rounds of a match, so I'm more than willing to spend a few provisions for a third one. It's always worth keeping in mind cards like Necromancy, Renew, and Operator when deckbuilding – ask yourself: are any of these cards so useful in a deck that it's worth jumping through hoops for more of them? In this case, I think the answer is yes. Recap

A good place to start when building a new deck is the win condition, as this is the basis that the rest of the deck is built around. Find a mechanic that you like, and it will lead you to the cards for your core package:

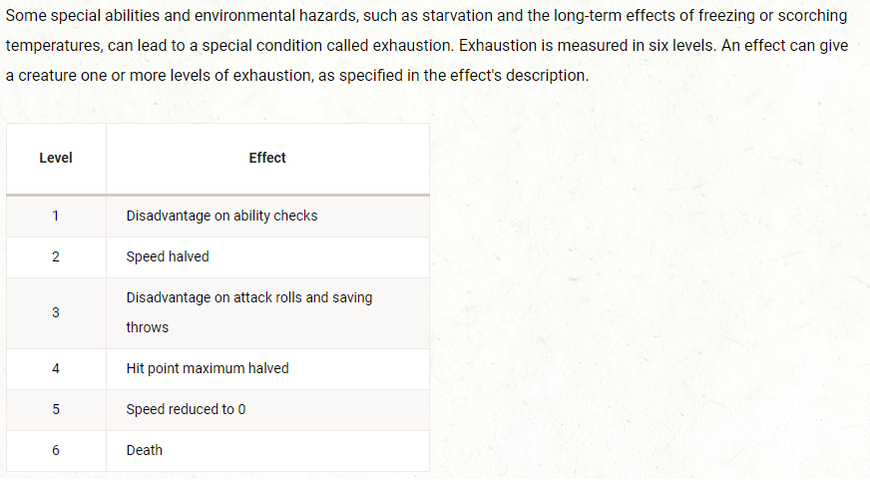

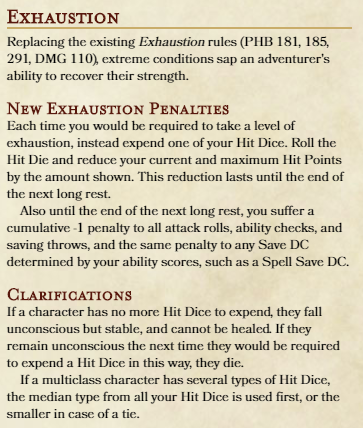

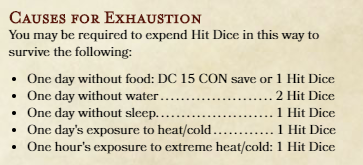

So, if we have a core package, what now? Well, if you recall the first article in this series, a deck needs a win condition, consistency, and versatility. We’ve just built the win condition, so next up is the rest of it: we need the consistency to ensure we have the cards we want, when we need them, and that they stay alive enough to be useful; and the versatility to handle whatever the opponent is doing. Join me next time for Deckbuilding #3 – Supporting Your Win Condition. The Exhaustion system in D&D 5th Edition is terrible. That's not a hot take, and is in fact a pretty generally accepted opinion, but today I thought I'd take a look at why it's so bad, and what could be done to fix it. So: what's wrong with exhaustion? 1. The penalties are weird As much as I love raw mechanical systems, flavour tie-in and things making intuitive sense is essential, particularly in a RP game like D&D. The penalties levied at different exhaustion levels aren't really related to each other. Levels 2 & 5 are movement-related, 4 & 6 are HP-related, and 1 & 3 only seem similar to each other until you note that ability checks are mostly non-combat while attacks and saves are almost exclusively combat-related. These penalties being so distinct means that at any point, one more level of exhaustion could be either crippling or irrelevant, dependent on the task at hand. 2. Penalties scale differently for each class The penalties affect each class very differently. For example, most wizards really won't care at all about the first two exhaustion levels—ability check disadvantage & halved movement—and can work around the third without too much trouble by using spells that target an enemy's saves rather than requiring an attack roll. Meanwhile, one exhaustion level can seriously affect a skill monkey's ability to do things outside of combat, or a grappler's ability to do things in combat, and two exhaustion levels may cripple a Barbarian or Paladin, classes that are only effective at close range. 3. It's part of the very half-baked mechanical support for exploration On page 8 of the Player's Handbook, the three pillars of D&D are listed as Exploration, Social Interaction & Combat. Of those three, the mechanics of 5e are very heavily combat-centric, and while there is some mechanical framework for social interaction, exploration for some reason got completely shafted. Now, my problems with this are numerous, and I'm sure I'll have a proper gripe about 5e's lack of exploration support at some point, but for now my point is that exhaustion is a mechanic largely built for exploration/survival, but without any actual exploration/survival systems it just sits there unused, orphaned by pretty much the entire rest of the book. Between the PHB and the Dungeon Master's Guide, exhaustion is given as a penalty for extreme temperatures, frigid water, starvation, dehydration, and travelling at a forced march. Xanathar's Guide to Everything adds exhaustion from long periods without a long rest, and temporary exhaustion from the spell Sickening Radiance. There's a single enemy from Princes of the Apocalypse, and to my knowledge that's pretty much it. No other spells, no monsters, no abilities... except for the PHB's first Barbarian subclass: the Berserker. Berserkers can take a level of exhaustion to make attacks with their bonus action for the duration of a single combat. Cool, fitting, powerful. However, in additon to the fact that the other subclass is the famed Totem Warrior, who can extend your resistance from physical to all damage, the Berserker really isn't an appealing subclass because exhaustion is so punishing. If you're gaining a level of exhaustion each time you use that ability in combat... that leads us to Number Four. 4. Exhaustion can only be removed by a long rest, and only one level at a time (or by the 5th-level spell Greater Restoration, which you can't get until 9th level, is only available to three classes, and is a pretty expensive trade for the Berserker ability). That's it. Those are the only ways to remove exhaustion, which means for practical purposes a Berserker can only gain their extra attack in one combat per long rest, is a mediocre grappler at best, and usually has disadvantage on ability checks, discouraging the player from participating in half the game. So, how would I change exhaustion? Exhaustion is one of the most frequently house-ruled or hand-waved parts of 5e. I've seen a number of house-rules, most of which seem to focus on adding things that cause exhaustion or changing the Berserker penalty. Here's my rework, redefining exhaustion with hit dice—another underused mechanic in 5e, directly tied to a character's endurance. These changes still function in line with the original design goals, creating pressure to rest, while impeding a character's abilities in a clear, understandable way that affects all classes in a similar manner.

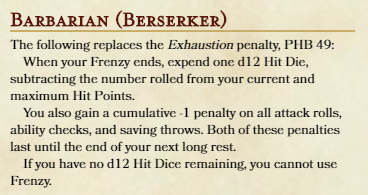

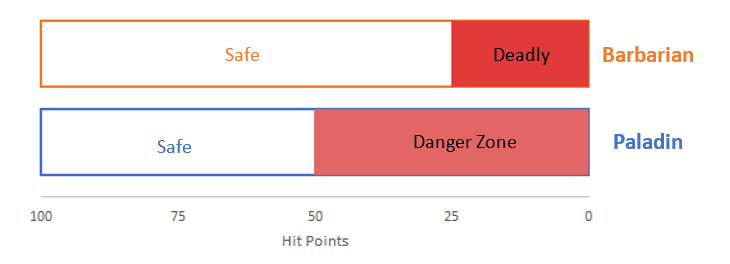

Tank: a character whose primary role is to absorb damage as a means of protecting allies 5e classes can tank damage in a few different ways. Paladins and Fighters can be ‘AC tanks’, who reduce incoming damage by being difficult to hit and having solid saving throws. Rogues and Monks, while they don’t usually serve as a blocker to protect allies, avoid damage through ‘dodge tanking’ – using abilities such as Uncanny Dodge, Evasion, and Deflect Missiles to nullify or reduce damage when hit. Moon Druids can be ‘sponge tanks,’ using their Wild Shape as a disposable HP pool to soak up huge amounts of damage. Barbarians are also ‘sponge tanks’ of a form, using damage resistance to halve incoming damage and simply, well, ‘tanking it’ with their massive HP pool. A cynic might say that if these methods were perfectly balanced, it really doesn’t matter which method you use – all will work out equally well in the long run – and the difference is more for the sake of appearance than anything else. Naturally, my strawman cynic is wrong, and for a number of reasons, but the one I’m looking at today is the impact of variance on planning. Let’s consider a Paladin and a Barbarian, in a heavily abstracted scenario. A monster hits for 50 damage. The Paladin has a 50% chance to avoid being hit, while the Barbarian will definitely get hit but only takes 50% of the damage. Both start with the same HP. Who dies first? At first glance, this might seem to be a draw. Both have the same expected (average) damage—25—so over an infinite number of attacks, we’d expect them to lose HP at the same rate. As they do not have infinite HP, however, the threshold becomes quite important. If they have 40 HP, the Paladin could die in one hit, while the Barbarian will not. If they have 20, the Barbarian is faced with certain death, while the Paladin might get lucky. Maybe this doesn’t appear that useful. If you’re really low, you want to be the Paladin; if you’re doing ok maybe you’d prefer to be the Barbarian – so what? Given you can’t just switch classes on the fly is it really true to say that one is better off in general? Yes. Yes it is. Imagine they have exactly 100 HP. Neither is at immediate risk of death, and on average we’d expect both to die on turn 4. How should each approach the encounter? For the Paladin, that’s a complex question. If they’re unlucky, they could die in two hits. They know they’re safe until they take damage the first time, but at that point all bets are off. Can the Paladin defeat their opponent quickly, or are they willing to gamble with their life? For the Barbarian, planning is much easier. They will die on the fourth turn. Can they defeat their opponent before then? If so, the combat is safe. If not, they should flee. In actual games, we have to account for variance from the damage dice as well. The monster could roll higher or lower than expected. Here, too, a Barbarian’s damage resistance reduces the variance: by halving the incoming damage, the difference between minimum and maximum damage rolls is less for the Barbarian than other classes. Less variance again means a better ability to predict outcomes, and more options in combat. The fundamental difference between these two modes of tanking is in outcome variance, and that affects their ability to plan an encounter and take calculated risks. With less uncertainty to account for, a Barbarian is better able to plan their actions in combat, and can expect a greater degree of success.

Two and a half years ago, Gwent was in beta, and I wrote an article on deckbuilding. People seemed to like it. A lot has changed since then. We now have two rows rather than three, two bronzes rather than three, and two colours rather than three (RIP silver). It seems that CD Projekt Red, like Valve, has a strange aversion to the first odd prime. Deckbuilding has changed a lot as well. The provision system has done away with gold card restrictions, removed the need to standardise card value, and added new incentives to pick weaker leaders. Despite this, however, the fundamentals of deckbuilding have remained the same. In this series of articles, I’ll take you through every stage of building a deck from scratch: from the initial concept, to building the core of a deck, rounding it out within the provisions system, and refining it through playtesting. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves! Today, we’re looking at decks more generally: an overview of what goes into a deck, and why. A deck needs three things. It needs a win condition, ways to improve the consistency of that win condition, and the versatility to adapt to whatever your opponent is doing. Let’s start at the top. A win condition is a deck’s game plan – how you intend to win a match. Usually, you can’t win without successfully executing your win condition. Win conditions can come in many forms, but are usually centred around a specific mechanic. For example, a Thrive deck’s win condition is its Thrive engines, which can be triggered continually by playing ever-larger cards to overwhelm the opponent with points. The win condition of the Northern Realms Swarm deck is to spam as many units across the board as possible, so that Bone Talisman, Vissegard, and Lyrian Scytheman play for massive value. Not all win conditions are centred around gaining points, however. Some focus on denying points to the opponent, for example by destroying all their engines, or setting up a huge damage combo. In any deck, what strategy or synergy do you use to ensure you have more points on the board than your opponent? The answer will usually define your main win condition.

Consistency in your deck is the key to having the card you want, when you need it. Inconsistent decks might still win matches, but will never be competitive. The more your deck relies on executing specific combos, the more you need to think about consistency. Cards that improve the consistency of your deck can be split into three rough categories: tutors, thinning, and protection. ‘Tutors’ (a term originally from Magic: The Gathering) allow you to pull other cards from your deck or graveyard. Some tutors give you great choice over what you pull – for example Royal Decree can tutor any unit in your deck. Others, like John Natalis, let you tutor any card matching a specific category. Marching Orders doesn’t give you a choice at all: it just gives you the lowest-power unit from your deck, but a carefully constructed deck can let you orchestrate which card that is. ‘Thinning’ is the term we use for cards like Roach or Foglet which reduce the size of your deck during the match, usually with the Draw or Summon keywords. This can be very important – a smaller deck increases the value of your draws and mulligans, as each is more likely to give the cards that you’re looking for. A quick note: although tutors and thinning use similar mechanics, they serve different purposes. Thinning is used early in the game, to remove weaker cards from your deck, increasing the value of your draws. By contrast, tutors are value plays, often best used in later rounds to find missing combo pieces or high-value powerplays. ‘Protection’: While tutors and thinning help you find the cards you need, protection cards keep them alive long enough to be useful. Many of Gwent’s most powerful units are balanced by some kind of vulnerability – those with Order abilities must survive a turn before they can be used, while engines (cards that generate more value over time) usually have low point values, making them vulnerable to removal. Playing a Defender first is a great way to make sure they stay safe! Other cards can protect a vulnerable unit by giving it a shield, armour, or boosting it by a few points. Some cards can even serve as ‘bait’ – if your opponent destroys them, they may have fewer options to deal with cards you play later in the round. Versatility helps you react to whatever the opponent is doing. Whether they’re setting up their own win condition or trying to disrupt yours, you need ways to respond. If the opponent is locking all your engines, you need a way to deal with that. If they’re throwing down high-value cards, you need a way to deal with that too. Every match is different, and these are the cards that help you adapt to changing conditions. The cards in your win condition are there to help you win; these cards help you not lose. Versatility cards come in many forms, but the uniting factor is this: how you use them depends on the match-up. Banish, Seize, and larger amounts of damage give you removal; Lock and Move let you control the cards you can’t remove outright. Purify basically just says ‘no’ to whatever your opponent just tried – it’ll neutralise their Defender, protect your unit from Poison or Bleeding, delete an enemy’s Shield or Vitality, or remove a Lock to give you your engine or Order ability back. A select few cards give you options in how to use them – different abilities when played in different rows, or when targeting an ally rather than targeting an enemy. For example, Trained Hawk gives you a control option on the Ranged row, or damage in Melee. Parasite can either boost an ally, or damage an enemy. Expensive tutors can provide both consistency and versatility, allowing you to tutor the right reactive card for the situation. So, what do these look like in practice? Let’s have a look at how these three components—win condition, consistency, and versatility—are represented within a deck. Below, I’ve taken lists for two of the strongest decks in the May/June meta, and marked each card by its function. Does it serve a win condition, add consistency to the execution of that strategy, or provide the versatility to adapt to each opponent? The first list is Nilfgaard’s much-feared Soldier-Ball deck. Its primary win condition is reliable point value: achieving high return for provisions, particularly through synergy between Soldier-tag units. 11 of the 25 cards serve this main package, plus the leader ability Imperial Formation, which effectively plays for 13 – eight points of boost, plus five for tutoring Affan Hillergrand. At the top of the list is the supremely powerful scenario Masquerade Ball, which not only plays well above its provision cost, but provides two charges of Poison – a mechanic that forms the centre of the win condition’s supporting package. In total, this package can apply Poison seven times from five cards, plus Vincent Van Moorlehem, who can destroy not only a Poisoned card, but one affected by any status: Shield, Lock, Poison, Doomed, Spying, Resilience, Bleeding, Vitality, and, rather importantly, Defender. Further tall removal comes in the form of Yennefer’s Invocation, and low-level removal is provided by several bronze cards, plus a conditional Seize from Sweers. Rounding out the versatility cards are a pair of cheap Lock cards, and the option of Purify from Van Moorlehem’s Cupbearer, if the player is willing to forgo one charge of Poison. The deck’s core package is quite consistent by itself. Most of the time, drawing one card from a particular category is much the same as drawing another, so the deck includes only two relatively limited tutors. Albrich must be used proactively, and leaves the chosen card on top of your deck rather than in your hand immediately, while Roderick of Dun Tynne is predictable only if the deck is low on gold cards in Round 3. The deck doesn’t require a huge amount of protection either, but the inclusion of a Defender can make cards like Maraal much more difficult to disrupt. Observations: The Soldier-Ball deck focuses on shutting down the opponent’s win condition, while its own, though it has a fairly modest point potential, is quite difficult to disrupt. Most cards, whether engines or Poison-focused removal, are devoted in some way to pure value, while specific card combos and sequencing receive little attention. The few consistency cards in the deck shouldn’t be underestimated however: though the player largely doesn’t mind which Poison or Soldier cards they’re holding, a small number of cards (Masquerade Ball, Yennefer’s Invocation…) carry a huge amount of value. The deck’s tutors may have very limited versatility, they greatly increase the consistency of finding these cards in each match. Overall, a deck that excels at disrupting the opponent’s plans without presenting vulnerabilities of its own, but lacks control over which cards are drawn, and when. The second list is the ever-popular Mystic Echo Harmony deck, whose primary win condition is to overwhelm the opponent with engines, mostly using the Harmony mechanic. The main package contains seven cards plus the leader ability Mystic Echo (used to copy Water of Brokilon), producing a total of 10 engines, and is supported by two high-value finishers: Great Oak and Barnabas Beckenbauer. The Dryad Rangers, in addition to being Harmony engines, also form the foundation of a Poison package rounded out by a pair of Forest Whisperers. A remarkably flexible Move package is built around Malena, who can move a card every turn. This allows her to control row-locked enemy cards, use Treant Boar’s damage ability every single turn, and even move Forest Whisperer to the Ranged row, allowing it to protect another unit with Shield. The deck lacks tall removal, but has many options to remove low-to-mid strength cards. Milaen’s 4 damage will kill most engines, while damage engines Pavko Gale and Treant Boar synergise well with the 2-3 damage dealt by the deck’s cheaper bronze cards, allowing the player to remove even 5-strength units in a single turn. Take particular note of Trained Hawk, a card of many functions. A Harmony engine, an uncommon Beast tag to reliably trigger other Harmony engines, control from an offensive Move option, and the flexibility to deal two damage if that’s not useful. Fantastic card, and despite its low provision cost, truly a cornerstone of this deck. Last: consistency. The Defender Figgis Merluzzo protects vulnerable engines, but the real star of the show here is the deck’s tutor package. Water of Brokilon is essential to the deck’s win condition, so the deck needs guaranteed access. Any of three cards will give access to Water of Brokilon—the card itself, Fauve, or Call of the Forest—so the player has an 80% chance of drawing one in their opening hand before mulligans, rising to a 99.5% chance to find access by Round Three. That might seem like overkill, but remember that any match without Water of Brokilon is pretty much a guaranteed loss, and no competitive deck can handle many of those. Once the player has access to Water of Brokilon, the remaining tutors give reliable access to the rest of the deck. Call of the Forest can tutor any unit the player needs from the entire deck. Isengrim’s Council is generally used to find whichever Dryad the player hasn’t drawn by Round 3, making the Poison package tremendously consistent. Fauve, if not used to find Water of Brokilon, can tutor either of the other two. Observations: The Mystic Echo Harmony deck is highly reliant not only on specific cards, but also on playing cards in a specific order to maximise Harmony value. As a result, consistency is vital, and so this list includes a number of particularly powerful and versatile tutors. The importance of playing cards in the right order also restricts the deck’s ability to respond to the opponent’s game plan – a control card played mid-sequence risks introducing the wrong tag at the wrong time, losing potential Harmony value. This sees the deck adopt a more inward focus, with disruptive cards usually either being Harmony engines as well (so that playing them reorders the sequence instead of disrupting it), or bearing a tag not shared by any of the deck’s engines (to minimise the potential value lost). A powerful and consistent deck, but a little limited in its ability to react to the opponent. Recap

So, a deck needs a win condition, the consistency to pull it off, and the versatility to disrupt your opponent’s win condition while protecting yours. When constructing a deck, consider each card: does it strengthen your game plan, its chance of coming together, or your ability to react to your opponent’s plays? Now, theory is all well and good, but how about deckbuilding in practice? Fear not! Next up, we’ll look at the actual hands-on process of building a deck from scratch. Over the next few articles, I’ll be building a deck with a rather unusual win condition, while explaining my process at each and every step along the way. Join me next time for Deckbuilding #2 – Building a Win Condition. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed