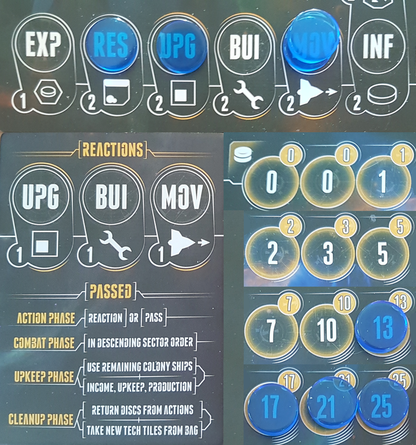

Well, it's been a couple of months since I wrote an analysis post, which makes it high time for another one! And, though the last post I made was also about Eclipse (2nd Edition), I'll be damned if it isn't the best-designed board game I've played in a long time, so here we go again! Last time, I wrote about how game designer Touko Tahkokallio reduced the combat disincentives that often plague similar games. This time, I want to take a look at something else he handled superbly well in Eclipse: passing. Eclipse, like most board games, is sequential and turn-based. One player takes their turn, then the next, and so on around the table. Each turn taken carries an increasing upkeep cost; a player may instead pass. Once all players have passed, the round ends: combats are resolved, income, upkeep and resource production are calculated, and new technologies become available before the next round begins and play resumes. This is all standard fare so far, and games that follow this pattern typically treat passing as a simple, functional mechanic: once they've taken as many turns as they want to or can afford, the player declares that they pass, and sits out the remainder of the round until all other players have done the same. This certainly isn't bad per se, and there's a lot to be said for not overcomplicating things unnecessarily, but I'm a huge fan of the systems Mr. Tahkokallio has put in place to turn passing into a complex and interesting decision, as important in a player's strategy as any other aspect of their game. In Eclipse, passing doesn't bar you from the rest of the round, but neither is it simply a 'no action this turn' option – any further turns taken before the end of the round carry heavy penalties. After passing, a player is restricted on future turns to 'reactions', a severely-limited version of the 'actions' taken normally. As a reaction, the player can only upgrade, build, or move (losing the options to research tech, explore new sectors, or move influence discs), and their upgrade/build/move is less efficient – a player might be able to move two or three ships with a normal action, but as a reaction is restricted to just one. Even worse, these reactions still increase the player's upkeep cost by the full amount, just like any other turn. In a long enough round, a player who played action - action - pass - reaction - pass - pass - reaction would be paying four turns worth of upkeep. Why, then, would a player pass before being certain they'd done everything they wanted to? Well, normally, you wouldn't. There is, however, a good reason they might pass earlier than is necessary, and one very big reason they might delay passing as long as possible. We'll start with the first one: why pass before you have to? The answer: first-to-pass bonuses. The first player to pass gains several advantages. First, you immediately receive a small monetary bonus, which could afford you a reaction if you're broke, or (much more efficiently), an extra action in the next round. Second, whoever passes first gets to start the next round, which comes with first pick of any new technologies, and places that player perfectly to eventually be the first to pass in that round as well, reaping these benefits all over again. Of course, you may have spotted already that if you pass first multiple rounds in a row, you've given up much of the benefit of the cash bonus – taking several extra turns down the line is less efficient in terms of upkeep, and a turn taken now gives immediate benefits. On the other hand, an extra turn in the current round will likely hand the first-to-pass bonuses to someone else. Perhaps you could pass early to deny others the bonus, then use the cash to cover the inefficiency of taking two reaction turns to do something that could otherwise be done in one... but even then there are no guarantees the round will last two more turns before everyone has passed. Of course, if you were to play a couple of extra turns this round after others have passed, you'll have less to do next round and will be more easily able to grab the first-to-pass bonus then... you can see how passing strategy becomes important! As for the reason you might delay passing as long as possible, even with the ever-mounting turn costs – the best time to invade a player is right after they pass. As reactions are only half- or one-third as efficient as actions, you'll be moving twice as many ships as they can scramble in defence, or upgrading your ship designs to exploit their vulnerabilities twice as fast as they can counter-upgrade in response. Of course, this is if you can afford to take all these actions in the first place... perhaps it was worth passing first several times to build up that cash reserve after all? In most other games, passing mechanics are functional, but unnoteworthy. As with so many elements of Eclipse, designer Touko Tahkokallio has gone the extra mile and turned it into an important, interactive, and rewarding aspect of the game. Absolutely phenomenal design.  I’ve just picked up a new boardgame: Eclipse (2nd Edition). As well as being fantastically fun to play, it’s also supremely well-designed. One element in particular is how Eclipse addresses some common 4X problems around instigating combat: attacker’s guilt and a higher combat risk for attackers. Particularly in boardgames, where players are sitting face-to-face, many players are uncomfortable with unprovoked aggression, even when the game requires it. Even a successful attack, if unprovoked, can leave the player feeling bad for victimising someone who did nothing to deserve it. This is natural, it is human, and, for designers, trying to avoid this problem can be frustrating. The root of the problem, I think, is the losses of the ‘victim’ relative to uninvolved parties. We don’t see the same reactions to profiteering, for example, where one player exploits the position of another to gain money/points/whatever without that player losing anything in the process. We also don’t see the same reactions in two-player games: the game unavoidably pits the two players against each other, so there is no victimisation. I believe that the problem arises specifically from the fact that the victim was targeted over other players, and has lost something. A related problem is the attacker’s risk: what if they attack and lose? Attacking usually costs something: in Eclipse, it costs turns, which translate to both time and money, and it risks ships, which have value. If the attacker then loses the battle, they’ve lost time, money, and ships, all to hand an opponent a bunch of points. This represents a far greater loss than the defender risks, and so disincentivises players from attacking unless they can muster overwhelming force. It is the uninvolved third parties who often get the best outcome. They risk nothing, lose nothing, come out objectively better than the battle’s loser, and may be in a good position to threaten the winner of the battle, who may have gained points or territory, but likely suffered some material losses. It may be better to sit back and wait for others to attack, than to go on the offensive yourself. These factors all discourage players from attacking, which can result in wargames involving rather less direct conflict than one might expect from the name. So, how did Touko Tahkokallio, Eclipse’s designer, solve these problems? Several factors combine to reduce the losses suffered by an unsuccessful defending player:

Fantastic design, and only a small part of what contributes to the game’s enjoyment! |

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed