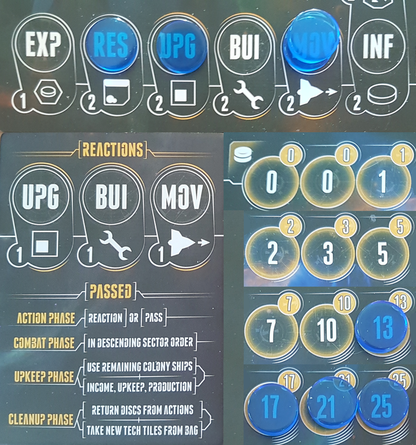

Well, it's been a couple of months since I wrote an analysis post, which makes it high time for another one! And, though the last post I made was also about Eclipse (2nd Edition), I'll be damned if it isn't the best-designed board game I've played in a long time, so here we go again! Last time, I wrote about how game designer Touko Tahkokallio reduced the combat disincentives that often plague similar games. This time, I want to take a look at something else he handled superbly well in Eclipse: passing. Eclipse, like most board games, is sequential and turn-based. One player takes their turn, then the next, and so on around the table. Each turn taken carries an increasing upkeep cost; a player may instead pass. Once all players have passed, the round ends: combats are resolved, income, upkeep and resource production are calculated, and new technologies become available before the next round begins and play resumes. This is all standard fare so far, and games that follow this pattern typically treat passing as a simple, functional mechanic: once they've taken as many turns as they want to or can afford, the player declares that they pass, and sits out the remainder of the round until all other players have done the same. This certainly isn't bad per se, and there's a lot to be said for not overcomplicating things unnecessarily, but I'm a huge fan of the systems Mr. Tahkokallio has put in place to turn passing into a complex and interesting decision, as important in a player's strategy as any other aspect of their game. In Eclipse, passing doesn't bar you from the rest of the round, but neither is it simply a 'no action this turn' option – any further turns taken before the end of the round carry heavy penalties. After passing, a player is restricted on future turns to 'reactions', a severely-limited version of the 'actions' taken normally. As a reaction, the player can only upgrade, build, or move (losing the options to research tech, explore new sectors, or move influence discs), and their upgrade/build/move is less efficient – a player might be able to move two or three ships with a normal action, but as a reaction is restricted to just one. Even worse, these reactions still increase the player's upkeep cost by the full amount, just like any other turn. In a long enough round, a player who played action - action - pass - reaction - pass - pass - reaction would be paying four turns worth of upkeep. Why, then, would a player pass before being certain they'd done everything they wanted to? Well, normally, you wouldn't. There is, however, a good reason they might pass earlier than is necessary, and one very big reason they might delay passing as long as possible. We'll start with the first one: why pass before you have to? The answer: first-to-pass bonuses. The first player to pass gains several advantages. First, you immediately receive a small monetary bonus, which could afford you a reaction if you're broke, or (much more efficiently), an extra action in the next round. Second, whoever passes first gets to start the next round, which comes with first pick of any new technologies, and places that player perfectly to eventually be the first to pass in that round as well, reaping these benefits all over again. Of course, you may have spotted already that if you pass first multiple rounds in a row, you've given up much of the benefit of the cash bonus – taking several extra turns down the line is less efficient in terms of upkeep, and a turn taken now gives immediate benefits. On the other hand, an extra turn in the current round will likely hand the first-to-pass bonuses to someone else. Perhaps you could pass early to deny others the bonus, then use the cash to cover the inefficiency of taking two reaction turns to do something that could otherwise be done in one... but even then there are no guarantees the round will last two more turns before everyone has passed. Of course, if you were to play a couple of extra turns this round after others have passed, you'll have less to do next round and will be more easily able to grab the first-to-pass bonus then... you can see how passing strategy becomes important! As for the reason you might delay passing as long as possible, even with the ever-mounting turn costs – the best time to invade a player is right after they pass. As reactions are only half- or one-third as efficient as actions, you'll be moving twice as many ships as they can scramble in defence, or upgrading your ship designs to exploit their vulnerabilities twice as fast as they can counter-upgrade in response. Of course, this is if you can afford to take all these actions in the first place... perhaps it was worth passing first several times to build up that cash reserve after all? In most other games, passing mechanics are functional, but unnoteworthy. As with so many elements of Eclipse, designer Touko Tahkokallio has gone the extra mile and turned it into an important, interactive, and rewarding aspect of the game. Absolutely phenomenal design.  I’ve just picked up a new boardgame: Eclipse (2nd Edition). As well as being fantastically fun to play, it’s also supremely well-designed. One element in particular is how Eclipse addresses some common 4X problems around instigating combat: attacker’s guilt and a higher combat risk for attackers. Particularly in boardgames, where players are sitting face-to-face, many players are uncomfortable with unprovoked aggression, even when the game requires it. Even a successful attack, if unprovoked, can leave the player feeling bad for victimising someone who did nothing to deserve it. This is natural, it is human, and, for designers, trying to avoid this problem can be frustrating. The root of the problem, I think, is the losses of the ‘victim’ relative to uninvolved parties. We don’t see the same reactions to profiteering, for example, where one player exploits the position of another to gain money/points/whatever without that player losing anything in the process. We also don’t see the same reactions in two-player games: the game unavoidably pits the two players against each other, so there is no victimisation. I believe that the problem arises specifically from the fact that the victim was targeted over other players, and has lost something. A related problem is the attacker’s risk: what if they attack and lose? Attacking usually costs something: in Eclipse, it costs turns, which translate to both time and money, and it risks ships, which have value. If the attacker then loses the battle, they’ve lost time, money, and ships, all to hand an opponent a bunch of points. This represents a far greater loss than the defender risks, and so disincentivises players from attacking unless they can muster overwhelming force. It is the uninvolved third parties who often get the best outcome. They risk nothing, lose nothing, come out objectively better than the battle’s loser, and may be in a good position to threaten the winner of the battle, who may have gained points or territory, but likely suffered some material losses. It may be better to sit back and wait for others to attack, than to go on the offensive yourself. These factors all discourage players from attacking, which can result in wargames involving rather less direct conflict than one might expect from the name. So, how did Touko Tahkokallio, Eclipse’s designer, solve these problems? Several factors combine to reduce the losses suffered by an unsuccessful defending player:

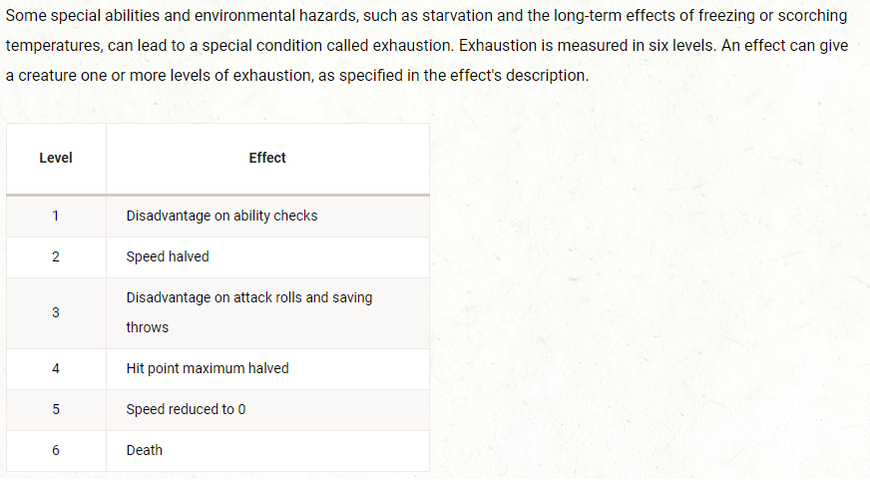

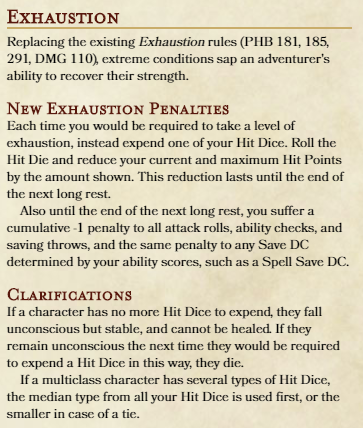

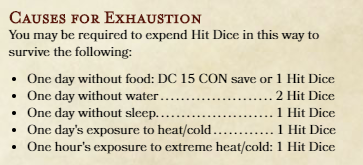

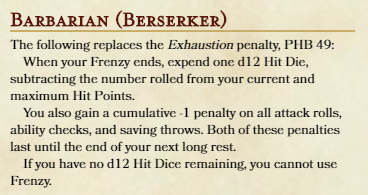

Fantastic design, and only a small part of what contributes to the game’s enjoyment! The Exhaustion system in D&D 5th Edition is terrible. That's not a hot take, and is in fact a pretty generally accepted opinion, but today I thought I'd take a look at why it's so bad, and what could be done to fix it. So: what's wrong with exhaustion? 1. The penalties are weird As much as I love raw mechanical systems, flavour tie-in and things making intuitive sense is essential, particularly in a RP game like D&D. The penalties levied at different exhaustion levels aren't really related to each other. Levels 2 & 5 are movement-related, 4 & 6 are HP-related, and 1 & 3 only seem similar to each other until you note that ability checks are mostly non-combat while attacks and saves are almost exclusively combat-related. These penalties being so distinct means that at any point, one more level of exhaustion could be either crippling or irrelevant, dependent on the task at hand. 2. Penalties scale differently for each class The penalties affect each class very differently. For example, most wizards really won't care at all about the first two exhaustion levels—ability check disadvantage & halved movement—and can work around the third without too much trouble by using spells that target an enemy's saves rather than requiring an attack roll. Meanwhile, one exhaustion level can seriously affect a skill monkey's ability to do things outside of combat, or a grappler's ability to do things in combat, and two exhaustion levels may cripple a Barbarian or Paladin, classes that are only effective at close range. 3. It's part of the very half-baked mechanical support for exploration On page 8 of the Player's Handbook, the three pillars of D&D are listed as Exploration, Social Interaction & Combat. Of those three, the mechanics of 5e are very heavily combat-centric, and while there is some mechanical framework for social interaction, exploration for some reason got completely shafted. Now, my problems with this are numerous, and I'm sure I'll have a proper gripe about 5e's lack of exploration support at some point, but for now my point is that exhaustion is a mechanic largely built for exploration/survival, but without any actual exploration/survival systems it just sits there unused, orphaned by pretty much the entire rest of the book. Between the PHB and the Dungeon Master's Guide, exhaustion is given as a penalty for extreme temperatures, frigid water, starvation, dehydration, and travelling at a forced march. Xanathar's Guide to Everything adds exhaustion from long periods without a long rest, and temporary exhaustion from the spell Sickening Radiance. There's a single enemy from Princes of the Apocalypse, and to my knowledge that's pretty much it. No other spells, no monsters, no abilities... except for the PHB's first Barbarian subclass: the Berserker. Berserkers can take a level of exhaustion to make attacks with their bonus action for the duration of a single combat. Cool, fitting, powerful. However, in additon to the fact that the other subclass is the famed Totem Warrior, who can extend your resistance from physical to all damage, the Berserker really isn't an appealing subclass because exhaustion is so punishing. If you're gaining a level of exhaustion each time you use that ability in combat... that leads us to Number Four. 4. Exhaustion can only be removed by a long rest, and only one level at a time (or by the 5th-level spell Greater Restoration, which you can't get until 9th level, is only available to three classes, and is a pretty expensive trade for the Berserker ability). That's it. Those are the only ways to remove exhaustion, which means for practical purposes a Berserker can only gain their extra attack in one combat per long rest, is a mediocre grappler at best, and usually has disadvantage on ability checks, discouraging the player from participating in half the game. So, how would I change exhaustion? Exhaustion is one of the most frequently house-ruled or hand-waved parts of 5e. I've seen a number of house-rules, most of which seem to focus on adding things that cause exhaustion or changing the Berserker penalty. Here's my rework, redefining exhaustion with hit dice—another underused mechanic in 5e, directly tied to a character's endurance. These changes still function in line with the original design goals, creating pressure to rest, while impeding a character's abilities in a clear, understandable way that affects all classes in a similar manner.

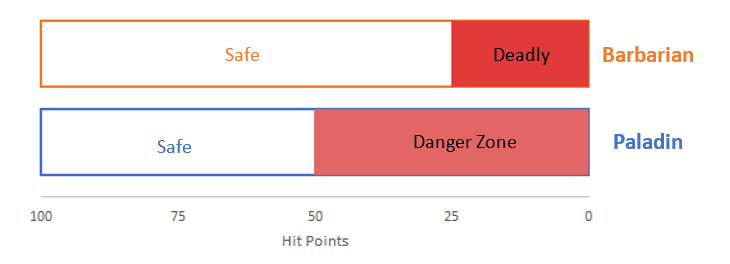

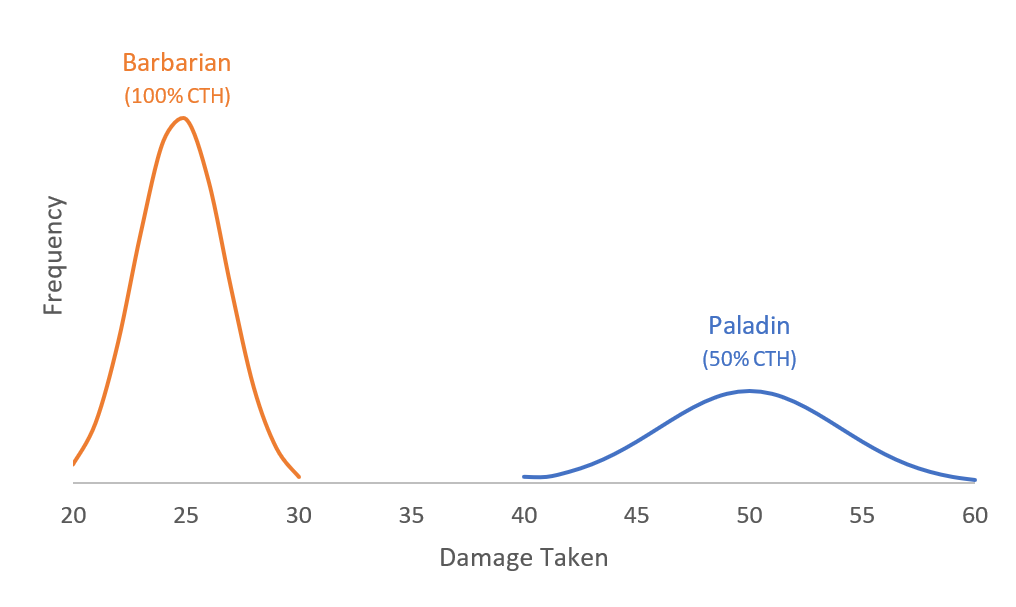

Tank: a character whose primary role is to absorb damage as a means of protecting allies 5e classes can tank damage in a few different ways. Paladins and Fighters can be ‘AC tanks’, who reduce incoming damage by being difficult to hit and having solid saving throws. Rogues and Monks, while they don’t usually serve as a blocker to protect allies, avoid damage through ‘dodge tanking’ – using abilities such as Uncanny Dodge, Evasion, and Deflect Missiles to nullify or reduce damage when hit. Moon Druids can be ‘sponge tanks,’ using their Wild Shape as a disposable HP pool to soak up huge amounts of damage. Barbarians are also ‘sponge tanks’ of a form, using damage resistance to halve incoming damage and simply, well, ‘tanking it’ with their massive HP pool. A cynic might say that if these methods were perfectly balanced, it really doesn’t matter which method you use – all will work out equally well in the long run – and the difference is more for the sake of appearance than anything else. Naturally, my strawman cynic is wrong, and for a number of reasons, but the one I’m looking at today is the impact of variance on planning. Let’s consider a Paladin and a Barbarian, in a heavily abstracted scenario. A monster hits for 50 damage. The Paladin has a 50% chance to avoid being hit, while the Barbarian will definitely get hit but only takes 50% of the damage. Both start with the same HP. Who dies first? At first glance, this might seem to be a draw. Both have the same expected (average) damage—25—so over an infinite number of attacks, we’d expect them to lose HP at the same rate. As they do not have infinite HP, however, the threshold becomes quite important. If they have 40 HP, the Paladin could die in one hit, while the Barbarian will not. If they have 20, the Barbarian is faced with certain death, while the Paladin might get lucky. Maybe this doesn’t appear that useful. If you’re really low, you want to be the Paladin; if you’re doing ok maybe you’d prefer to be the Barbarian – so what? Given you can’t just switch classes on the fly is it really true to say that one is better off in general? Yes. Yes it is. Imagine they have exactly 100 HP. Neither is at immediate risk of death, and on average we’d expect both to die on turn 4. How should each approach the encounter? For the Paladin, that’s a complex question. If they’re unlucky, they could die in two hits. They know they’re safe until they take damage the first time, but at that point all bets are off. Can the Paladin defeat their opponent quickly, or are they willing to gamble with their life? For the Barbarian, planning is much easier. They will die on the fourth turn. Can they defeat their opponent before then? If so, the combat is safe. If not, they should flee. In actual games, we have to account for variance from the damage dice as well. The monster could roll higher or lower than expected. Here, too, a Barbarian’s damage resistance reduces the variance: by halving the incoming damage, the difference between minimum and maximum damage rolls is less for the Barbarian than other classes. Less variance again means a better ability to predict outcomes, and more options in combat. The fundamental difference between these two modes of tanking is in outcome variance, and that affects their ability to plan an encounter and take calculated risks. With less uncertainty to account for, a Barbarian is better able to plan their actions in combat, and can expect a greater degree of success.

|

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed